How 1930s Redlining Still Determines Where Liquor Stores Are Concentrated Today

In 2026, if you want to predict where liquor stores concentrate in American cities, don't look at current demographics or zoning laws. Look at maps drawn by federal agencies in the 1930s. Those Depression-era documents—created explicitly to deny Black Americans access to homeownership—still determine with disturbing precision where alcohol retailers cluster today.

The correlation isn't subtle. Neighborhoods that the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) outlined in red ink and labeled "hazardous" because Black people lived there contain SOURCE three to four times more liquor stores per capita than neighborhoods outlined in green and rated "best" for their white, affluent populations. This pattern holds across virtually every American city where HOLC created maps between 1935 and 1940.

The 1930s federal housing policies didn't just deny Black Americans mortgages. They established geographic patterns of commercial investment, disinvestment, and exploitation that persist nearly a century later. Understanding how redlining continues controlling liquor store placement requires examining both the deliberate racism of New Deal programs and the mechanisms through which those discriminatory decisions became permanently embedded in urban landscapes.

The Home Owners' Loan Corporation and "Residential Security Maps"

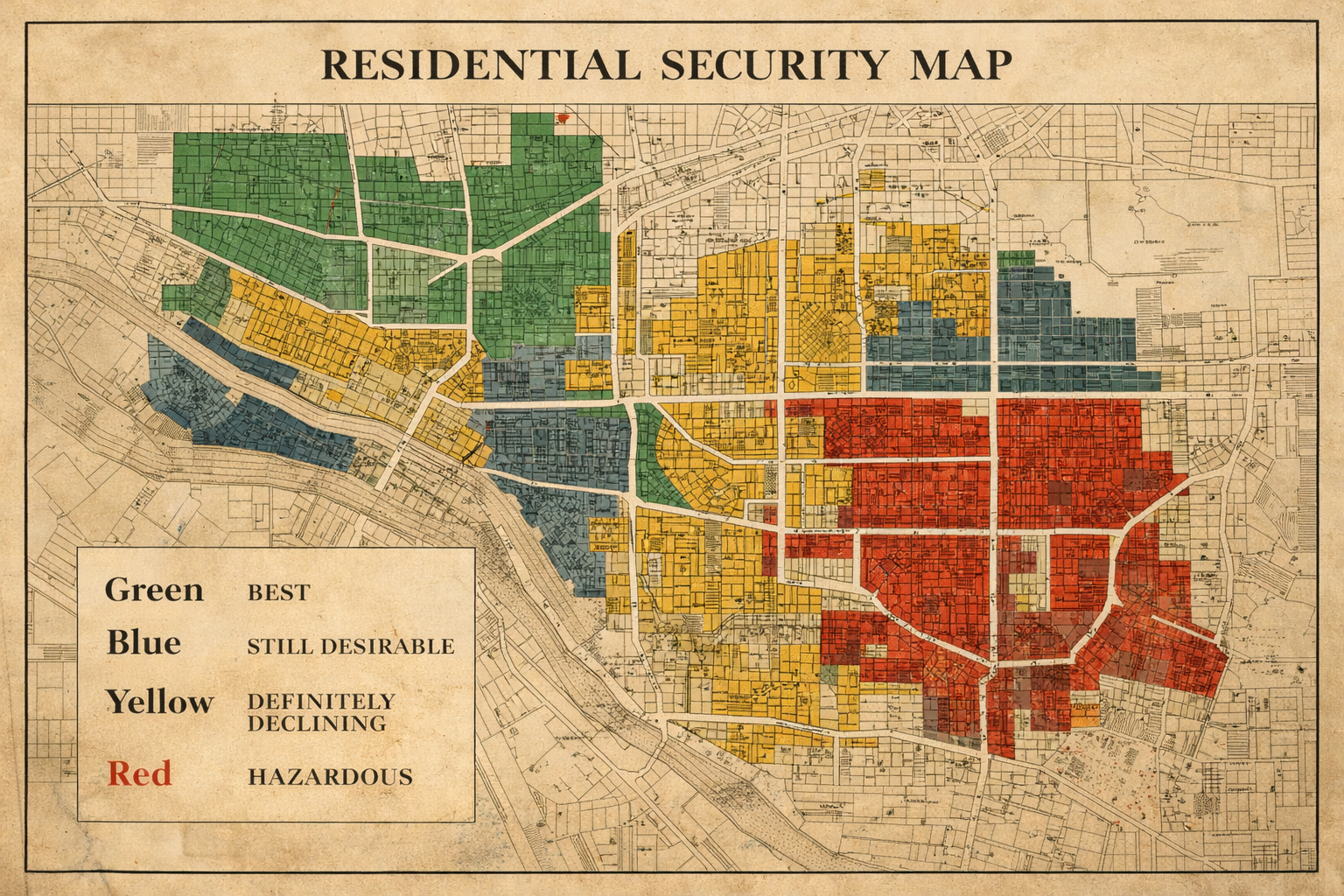

The HOLC was created in 1933 as part of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal to stabilize the housing market during the Depression. The agency refinanced mortgages for homeowners facing foreclosure and aimed to restore confidence in residential lending. To guide future lending decisions, HOLC created "residential security maps" for 239 American cities between 1935 and 1940.

These maps divided cities into neighborhoods color-coded by perceived lending risk. Green areas were rated "best"—suitable for mortgage lending with minimal risk. Blue areas were "still desirable." Yellow areas were "definitely declining." Red areas were "hazardous"—places where SOURCE mortgage lending should be avoided entirely.

Artistic depiction of a 1930s HOLC residential security map. Federal agencies color-coded neighborhoods from green ('best') to red ('hazardous') based explicitly on racial composition. These maps—created between 1935 and 1940 for 239 American cities—continue determining liquor store concentrations today.

The criteria for these ratings were explicitly racist. HOLC surveyors noted the presence of Black residents as a primary factor lowering neighborhood ratings. A neighborhood could have well-maintained housing, low crime, good schools, and stable employment—but the presence of even a small Black population pushed it into the red zone. Survey forms included categories for recording racial composition, and neighborhoods with any "Negro" residents were systematically downgraded.

The language in HOLC surveys made the racism explicit. Richmond, Virginia surveys described areas as "hopelessly heterogeneous" due to Black residents. Detroit surveys warned that neighborhoods with African Americans had "no future." Brooklyn surveys stated that Black presence created "detrimental influences" making areas unsuitable for investment. San Francisco surveys recommended against lending in areas where "Oriental infiltration" had occurred.

These weren't subjective assessments by individual loan officers. This was systematic federal policy implemented by trained surveyors using standardized forms designed by government agencies. The racism was institutional, deliberate, and comprehensive.

From Housing Discrimination to Commercial Patterns

The immediate effect of redlining was to deny Black Americans access to homeownership and mortgage credit. Banks refused to lend in red-outlined areas. The Federal Housing Administration, created in 1934, adopted HOLC's color-coded approach and explicitly refused to insure mortgages in neighborhoods with Black residents. Private lenders followed federal guidance, treating redlined areas as untouchable.

But redlining's effects extended far beyond housing finance. When neighborhoods were designated "hazardous," all forms of investment fled. Banks wouldn't lend for small business development. Insurance companies charged higher premiums or refused coverage entirely. Retail chains avoided opening stores. Property maintenance declined as owners couldn't secure loans for improvements.

This created a vacuum of legitimate commercial activity. National grocery chains, department stores, and quality retailers stayed out of redlined areas. The absence of mainstream commercial investment created opportunities for businesses that other neighborhoods didn't want or that exploited the limited options available to residents denied access to better areas.

Liquor stores filled this vacuum systematically. State and local liquor licensing authorities concentrated permits in redlined neighborhoods where resistance from homeowners and business associations was weakest. Areas outlined in green fought liquor store licenses aggressively through zoning boards and neighborhood associations. Areas outlined in red lacked the political power and institutional resources to resist.

The pattern wasn't accidental. Liquor licensing decisions explicitly considered neighborhood characteristics that mirrored redlining criteria. Licensing authorities asked whether proposed locations were in "declining" areas, whether property values were low, whether commercial vacancies were high—all conditions created by redlining itself. Then they approved liquor licenses in those very areas, citing the same characteristics that redlining had produced.

The Modern Data Confirms Historical Patterns

Contemporary research demonstrates that 1930s redlining maps predict current liquor store density with remarkable precision. A SOURCE 2019 study analyzing liquor store locations across multiple cities found that HOLC "D" grade (redlined) neighborhoods contain significantly higher concentrations of alcohol retailers than "A" grade (green) neighborhoods, even after controlling for current demographics, income levels, and population density.

In Los Angeles, neighborhoods rated "hazardous" by HOLC in 1939 have more than four times the liquor store density of neighborhoods rated "best." In Baltimore, redlined areas from 1937 show three times higher alcohol retailer concentration compared to green areas. The pattern repeats in Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis—every major city where researchers have compared HOLC maps to current liquor store locations.

The correlation holds even in neighborhoods where racial composition has changed since the 1930s. Areas that were redlined because they housed Black populations in 1935 but have since gentrified still show elevated liquor store concentrations compared to areas that were never redlined. The commercial patterns established in response to 1930s federal policy persist regardless of subsequent demographic shifts.

This isn't about current zoning ordinances or recent planning decisions. Cities have updated zoning codes dozens of times since the 1930s. Yet liquor store concentrations remain anchored to Depression-era federal housing discrimination maps. The explanation lies in how initial placement decisions create self-reinforcing patterns.

How Redlining Became Permanent

Once liquor stores concentrated in redlined neighborhoods, multiple mechanisms locked that pattern in place permanently.

Existing nonconforming uses: When cities later adopted zoning that would prohibit new liquor stores in residential areas, existing stores were "grandfathered" as legal nonconforming uses. A store licensed in 1940 in a redlined neighborhood remains legal today even if current zoning wouldn't permit a new liquor license in that location. The stores placed during the redlining era became permanent fixtures.

Transfer and succession: Liquor licenses in most states can be sold, transferred, or passed to new owners. A license granted in 1945 for a location in a redlined area continues operating in 2025 under the tenth or fifteenth successive owner. The license itself—granted based on redlining-era neighborhood characteristics—persists across decades regardless of neighborhood changes.

Market concentration: Once multiple liquor stores concentrate in an area, additional retailers locate nearby to capture the established customer base. The initial clustering driven by redlining attracts more alcohol retailers, creating self-reinforcing commercial patterns. Areas with high liquor store density attract more liquor stores; areas with low density remain underserved.

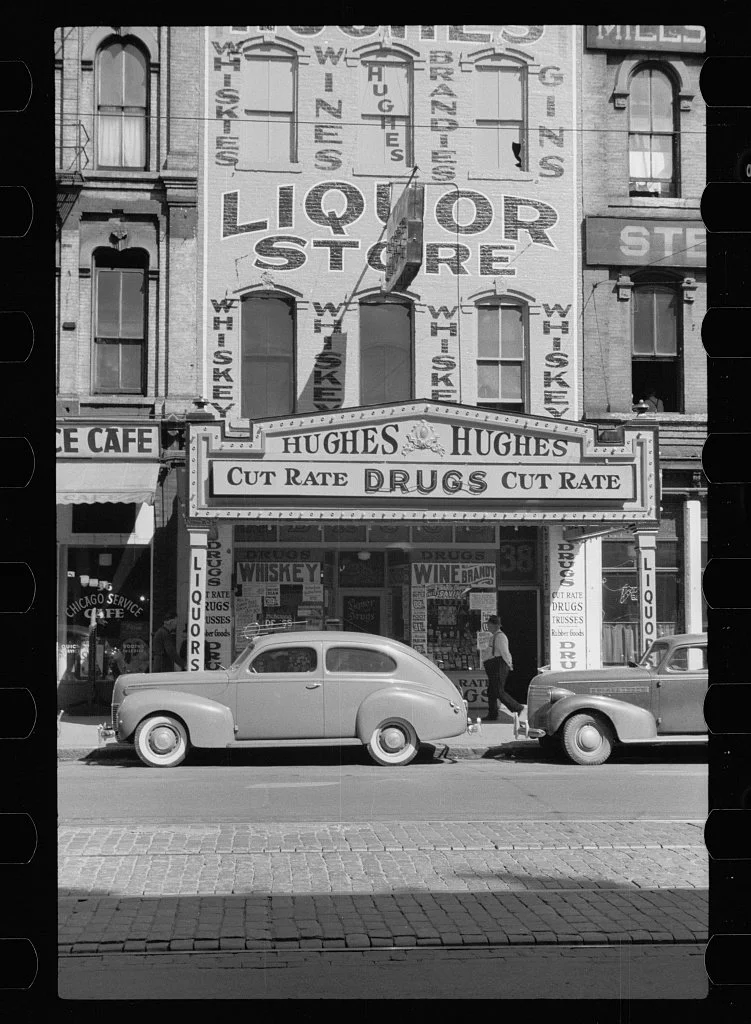

Liquor store in Minneapolis's Gateway District, September 1939. Photographer John Vachon documented this urban neighborhood just four years after HOLC created redlining maps. The Gateway District—a low-income area where liquor stores concentrated—exemplifies the commercial patterns that federal housing discrimination established and that persist today. Photo by John Vachon, Library of Congress FSA-OWI Collection, public domain.

Property values and vacancy: Redlining depressed property values in designated areas, making commercial rent cheaper than in green-lined neighborhoods. Liquor retailers seeking low-cost locations naturally concentrate where rent is cheapest—which remains the same neighborhoods redlining designated as "declining" ninety years ago.

Community resistance capacity: Wealthier neighborhoods that escaped redlining maintain organized opposition to new liquor licenses through neighborhood associations, legal challenges, and political pressure on licensing boards. Poorer neighborhoods that were redlined lack comparable organizational resources to fight license applications. This perpetuates the unequal distribution.

Path dependence: Urban development follows established patterns. Once a commercial corridor develops liquor-heavy retail character, it continues that pattern. Property owners lease to similar tenants. Customers expect certain types of businesses. The commercial identity established during the redlining era becomes self-perpetuating.

The combined effect is that decisions made by federal agencies in the 1930s continue determining commercial landscapes in 2025. The racism has been thoroughly laundered through decades of ostensibly race-neutral market processes, but the underlying pattern traces directly to explicit federal discrimination.

The Public Health Consequences

The concentration of liquor stores in historically redlined neighborhoods isn't just a historical curiosity—it produces measurable public health harms today.

Research demonstrates strong correlations between SOURCE liquor store density and alcohol-related problems. Areas with high concentrations of alcohol retailers show elevated rates of alcohol dependency, drunk driving arrests, alcohol-related emergency room visits, and alcohol-attributable deaths. The relationship persists even controlling for individual-level factors like income and education.

The mechanism is straightforward: greater availability increases consumption. When liquor stores saturate a neighborhood, alcohol becomes more accessible, purchasing becomes more convenient, and prices often fall due to competition. These factors all increase consumption levels, which increases alcohol-related harms.

Children in neighborhoods with high liquor store density face particular risks. They encounter more alcohol advertising, see more public intoxication, witness more alcohol-related violence, and have easier access to alcohol through older peers or inadequate age verification at oversaturated retailers. Adolescents in areas with high alcohol outlet density show SOURCE increased rates of alcohol initiation and heavy drinking.

The health disparities created by liquor store concentration compound other health inequities facing communities of color. Redlined neighborhoods already experience higher rates of chronic disease, lower access to healthcare, greater environmental pollution, and more limited access to healthy food. Adding elevated alcohol-related harms creates additional health burdens on populations already facing systemic disadvantages.

Public health researchers have documented these disparities for decades. What's increasingly clear is that the disparities aren't random or culturally determined—they're the direct result of federal housing policy from the 1930s continuing to shape commercial landscapes today.

The Economic Exploitation Continues

The liquor industry's concentration in historically redlined neighborhoods represents ongoing economic exploitation rooted in Depression-era racism. Alcohol retailers extract substantial revenue from these communities while providing minimal employment or economic benefit.

Liquor stores in low-income neighborhoods are typically owned by individuals or corporations residing elsewhere. Profits flow out of the community rather than circulating locally. The businesses provide few jobs—most liquor stores employ only one or two workers—and those jobs are typically low-wage with no benefits.

Meanwhile, the presence of concentrated liquor stores depresses property values and discourages other commercial investment. Retail corridors dominated by alcohol outlets struggle to attract restaurants, grocery stores, clothing retailers, or other businesses that would provide greater employment and community benefit. The liquor store concentration becomes self-perpetuating—driving away alternative commercial development while attracting more alcohol retailers.

The advertising accompanying liquor store concentration constitutes additional exploitation. Alcohol companies spend heavily marketing to communities where stores concentrate, creating brand awareness and product demand. The marketing often specifically targets Black and Latino consumers with advertising that wouldn't be acceptable in white neighborhoods, using imagery and messaging that exploits cultural symbols while promoting products that harm community health.

This pattern—extracting revenue while providing minimal benefit and imposing health costs—mirrors the broader economic exploitation that redlining enabled. The neighborhoods designated "hazardous" in the 1930s became zones where extractive businesses could operate with minimal resistance, and that designation continues determining which communities face concentrated alcohol marketing and availability today.

Zoning and Licensing Reforms Face Path Dependence

Cities attempting to address liquor store concentration through zoning or licensing reforms encounter obstacles created by the very patterns they're trying to change. Existing stores enjoy legal protection as nonconforming uses. Licenses carry substantial value and can't be revoked without compensation. Efforts to limit new licenses face opposition from the liquor industry and from existing retailers who benefit from restricted competition.

Some cities have attempted minimum spacing requirements—prohibiting new liquor licenses within a certain distance of existing stores or schools. These ordinances may prevent additional concentration but do nothing about existing oversaturation. In neighborhoods with dozens of grandfathered liquor stores, spacing requirements mainly prevent new competition rather than reducing overall density.

Conditional use permits—requiring liquor license applicants to demonstrate community support—can give neighborhoods more control over new licenses. But in oversaturated areas, the damage is already done. Communities need mechanisms to reduce existing liquor store density, not just slow new growth. State laws typically provide no such mechanisms.

Some jurisdictions have explored "deemed approved" status removal—identifying stores operating in violation of conditions imposed when licenses were granted, then revoking those licenses. This approach faces legal challenges and affects only the small percentage of stores with enforceable conditions attached to their licenses.

The most direct approach—using eminent domain to purchase and close liquor stores in oversaturated areas—requires substantial public funding and faces political opposition from the liquor industry. Few cities have attempted this strategy, and those that have managed only small-scale interventions affecting a handful of stores.

The fundamental obstacle is that patterns established by 1930s federal policy have become entrenched through property rights, market dynamics, and political resistance. Reversing those patterns requires confronting not just current liquor store owners but the accumulated weight of ninety years of path-dependent development.

Legal Challenges to Addressing Redlining's Legacy

Efforts to reduce liquor store concentration in historically redlined neighborhoods face significant legal constraints rooted in the same property rights that protect all commercial activity.

Liquor licenses are considered property with substantial market value. In California, liquor licenses sell for $50,000 to $400,000 depending on type and location. In Florida, licenses trade for $100,000 to $1 million. Any action reducing license value or revoking licenses without cause faces legal challenge as an unconstitutional taking requiring just compensation.

This creates a perverse dynamic: the more valuable licenses have become due to artificial scarcity and market concentration, the more expensive it becomes for governments to reduce liquor store density. The very patterns created by discriminatory policy have generated property interests that now protect those patterns from reform.

Zoning ordinances that would prohibit new liquor stores in residential areas face challenges under state liquor licensing laws, which typically supersede local zoning authority. Many states grant liquor licensing control to state agencies rather than local governments, limiting cities' ability to regulate alcohol retail through land use planning.

Even where local governments have authority to deny new licenses based on overconcentration, the definition of "overconcentration" becomes contested. What density of liquor stores constitutes oversaturation? Compared to what baseline? Historical patterns created by redlining have normalized extraordinarily high liquor store densities in some neighborhoods, making it difficult to argue legally that additional stores would create overconcentration when dozens already exist.

Civil rights claims against liquor licensing policies face obstacles under current constitutional doctrine. Proving intentional discrimination requires showing that current decision-makers acted with discriminatory intent—difficult when the discriminatory pattern was established by federal agencies ninety years ago and has simply been maintained through facially neutral processes.

Disparate impact claims—arguing that policies have discriminatory effects regardless of intent—have found more success in some contexts but face limitations in liquor licensing. Courts have been reluctant to second-guess state authority over alcohol regulation, and liquor industry defendants can point to multiple non-discriminatory reasons for license placement decisions even when the overall pattern clearly tracks historical redlining.

Community Organizing Against Oversaturation

Despite legal obstacles, community organizations in historically redlined neighborhoods have fought liquor store concentration through protest, political pressure, and strategic use of available regulatory processes.

In South Los Angeles, community groups have organized to oppose new liquor licenses by flooding public hearings, documenting neighborhood impacts, and mobilizing political pressure on city council members. These campaigns have successfully blocked some new licenses and created political costs for officials who approve additional stores in oversaturated areas.

In Baltimore, residents of redlined neighborhoods have used community benefit agreements to extract concessions from liquor license applicants—requiring stores to limit hours, restrict certain products, or fund community programs in exchange for neighborhood support. While these agreements don't reduce overall store density, they give communities some leverage over how existing stores operate.

In Oakland, community organizations have mapped liquor store locations against HOLC redlining maps, creating powerful visual documentation of how 1930s federal policy continues shaping neighborhoods today. This mapping work has been used to support zoning reforms and to educate the public about structural racism's ongoing effects.

Grassroots organizing faces significant obstacles. Liquor license hearings occur with minimal notice, often during working hours when community members can't attend. Licensing processes are technical and legalistic, creating barriers for non-expert participation. The liquor industry has resources to hire lawyers and consultants, while community groups operate on volunteer labor.

Moreover, fighting individual license applications addresses symptoms rather than underlying patterns. Even successful opposition to one new license does nothing about the dozens of existing stores already oversaturating the neighborhood. Communities need systemic solutions, not just victories in individual cases.

The Role of State Liquor Control

State alcoholic beverage control agencies bear responsibility for liquor licensing patterns that mirror 1930s redlining, yet few have acknowledged this legacy or taken action to address it.

Most state ABC agencies claim to apply objective criteria when evaluating license applications—population density, existing license concentration, documented community needs. But these "objective" criteria systematically reproduce historical patterns because they take existing conditions as givens rather than questioning how those conditions originated.

When a licensing board considers whether an area needs an additional liquor store, it looks at current demographics, crime rates, and existing commercial character. An area that was redlined in 1935 will show high existing liquor store density, which might suggest the market is saturated. But that same high density might also suggest strong demand, justifying another license. Either way, the board's analysis begins from conditions created by historical discrimination without examining that history.

State agencies have tools to address overconcentration but rarely use them aggressively. Many states allow denial of new licenses based on "public convenience and necessity" or "overconcentration" but apply these standards inconsistently and typically only in response to specific community opposition rather than as systematic policy.

A few states have attempted reforms. California's Alcoholic Beverage Control has designated certain areas as "overconcentrated" and applies stricter scrutiny to new license applications in those zones. But even this modest reform grandfathers existing licenses and does nothing to reduce current oversaturation.

Comprehensive reform would require state ABC agencies to acknowledge that current liquor licensing patterns reflect historical discrimination, conduct systematic analysis of how redlining shaped alcohol retail geography, and implement programs to reduce concentration in historically disadvantaged neighborhoods. No state has undertaken this work.

The Federal Government's Responsibility

The federal government created the redlining system that continues determining liquor store placement today. Federal agencies have never acknowledged this legacy or taken responsibility for remedying it.

HOLC was dissolved in 1951 after refinancing over one million mortgages. The agency's maps were filed away in National Archives storage. For decades, few people outside academic researchers examining housing discrimination knew the maps existed. The federal government made no effort to study the maps' long-term effects, address the harms they caused, or remedy the patterns they established.

When the maps became more widely known in the 1990s and 2000s through digitization projects, federal agencies still took no action. HUD has acknowledged the discriminatory nature of past federal housing policies but has implemented no programs specifically addressing the commercial patterns those policies created.

Federal agencies could take multiple actions to address redlining's legacy in liquor store concentration. HUD could fund research documenting the correlation between HOLC maps and current alcohol outlet density. The CDC could include analysis of historical redlining in community health assessments and target public health interventions to areas affected by federal housing discrimination. The Justice Department could investigate whether liquor licensing patterns violating disparate impact standards under fair housing law.

More directly, federal funding could support community-based efforts to reduce liquor store concentration in historically redlined neighborhoods. Grants could enable cities to purchase and close stores in oversaturated areas, provide alternative economic development in affected neighborhoods, or support legal challenges to discriminatory licensing practices.

None of this has happened. The federal government created the problem, benefited from excluding Black Americans from homeownership and wealth-building, and now disclaims responsibility for the ongoing consequences.

Why This Matters in 2025

Understanding that 1930s redlining continues determining liquor store placement today matters for several reasons.

First, it demonstrates that structural racism isn't just historical—it's actively shaping communities right now. The maps drawn by New Deal agencies weren't just artifacts of a less enlightened past. They're blueprints that still determine commercial development patterns, public health outcomes, and economic opportunities ninety years later.

Second, it reveals how discrimination gets laundered through ostensibly neutral processes. Nobody making liquor licensing decisions today explicitly says "concentrate stores in Black neighborhoods." But by accepting existing patterns as normal, applying "objective" criteria that take discriminatory conditions as givens, and failing to examine how current distributions originated, modern decision-makers reproduce 1930s racism through facially neutral administration.

Third, it shows why remedying historical discrimination requires active intervention, not just ending discriminatory policies. Even if every liquor licensing decision made since 1950 were completely race-neutral (which they weren't), the patterns established by federal discrimination in the 1930s would persist through market forces and legal protections for existing uses. Correcting historical wrongs requires deliberate action to undo their effects.

Fourth, it illustrates how multiple systems of discrimination reinforce each other. Redlining didn't just affect housing—it shaped commercial development, which affected economic opportunity, which influenced health outcomes, which determined educational access, which limited wealth accumulation, creating multiple mechanisms through which 1930s federal policy continues disadvantaging the same communities today.

Finally, it demonstrates the inadequacy of current civil rights frameworks for addressing structural discrimination. When harm is caused by federal agencies ninety years ago but perpetuated through decades of facially neutral decisions, who can be sued? What remedy can courts order? How can victims prove discrimination when no current actor harbors discriminatory intent?

Toward Solutions

Addressing how 1930s redlining determines current liquor store concentration requires interventions at multiple levels.

Documentation: Cities and states should systematically map current alcohol outlet density against HOLC redlining maps, documenting the correlation and making findings public. This creates evidentiary foundation for reform and public awareness of the issue.

Licensing reform: State ABC agencies should adopt policies explicitly considering whether license applications would perpetuate patterns rooted in historical discrimination. Areas showing correlation between HOLC redlining and current overconcentration should receive heightened protection against new licenses.

Density reduction: Cities should develop programs to reduce liquor store concentration in historically redlined neighborhoods through purchase and closure of willing sellers, stricter enforcement of license conditions, and strategic non-renewal when violations occur.

Community empowerment: Licensing processes should give affected communities meaningful power to oppose new licenses and challenge existing ones. Community benefit agreements should be required for all licenses in historically disadvantaged areas.

Federal accountability: The federal government should fund research on redlining's legacy in commercial patterns, support local efforts to address alcohol outlet concentration, and acknowledge responsibility for creating the patterns it now must help remedy.

Reparative investment: Public and private investment should flow to historically redlined neighborhoods to support alternative commercial development that benefits community health rather than exploiting vulnerable populations.

None of these solutions is easy. All face legal obstacles, political resistance, and resource constraints. But continuing to pretend that liquor store concentration in Black and Latino neighborhoods is coincidental—rather than the direct result of federal housing discrimination policy—is both intellectually dishonest and morally unacceptable.

When you see a liquor store in a low-income neighborhood of color today, you're not seeing a free market outcome. You're seeing a 1930s federal map, drawn by New Deal agencies, explicitly designed to deny Black Americans the opportunity to build wealth through homeownership, continuing to shape that same community's commercial landscape ninety years later.

The maps have yellowed. The language has been laundered. The agencies have been dissolved. But the red lines remain, determining who lives with liquor stores on every corner and who doesn't, who faces elevated health risks and who's protected, who builds wealth and who watches profits flow elsewhere—all based on decisions made before most Americans alive today were born.

That's not ancient history. That's the present, manufactured by the past, maintained by inaction, and perpetuated by refusal to acknowledge how current patterns originated. Understanding this history doesn't erase ninety years of accumulated harm. But it's the necessary first step toward finally undoing what the federal government created and what every subsequent generation has chosen to accept.