Harlem's Whiskey Rebellion: When Civil Rights Activists Fought the Liquor Industry's Racism

The story of the Civil Rights Movement typically centers on the 1950s and 1960s—Montgomery bus boycott, lunch counter sit-ins, Freedom Rides, March on Washington. But decades earlier, Harlem activists were pioneering the tactics that would define civil rights activism: organized boycotts, economic pressure campaigns, mass protests, and demands for both employment and dignity.

Their target was the liquor industry—an industry that made enormous profits selling to Black customers while refusing to hire Black workers, excluding Black-owned distributors, and denying advertising revenue to Black newspapers. The campaign became known as Harlem's "Whiskey Rebellion," and it lasted from the 1930s through the 1960s, achieving victories that have been largely erased from civil rights history.

The Economics of Exploitation

By the 1930s, Harlem had become the cultural and economic capital of Black America. Its population had exploded during the Great Migration, creating a concentrated market of Black consumers with significant purchasing power. Liquor companies understood this market's value—they located stores throughout Harlem, advertised heavily to Black customers, and generated substantial profits from Black neighborhoods.

But they refused to hire Black workers. Liquor stores in Harlem were owned by white proprietors, staffed entirely by white employees, supplied by white-owned distributorships, and serviced by white delivery drivers. The profits flowed out of Harlem while employment opportunities stayed closed to the community creating the profits. SOURCE

This economic model was deliberate and systematic. The liquor industry post-Prohibition had learned from pre-Prohibition strategies of racial exclusion. When Prohibition ended in 1933, the industry reconstructed itself along explicitly segregated lines—white-owned companies selling to Black customers while denying Black Americans access to employment, ownership, or economic participation.

The advertising pattern revealed the exploitation clearly. Liquor companies spent heavily advertising in mainstream white publications but refused to place ads in Black newspapers like the Amsterdam News, the Age, or the People's Voice. They wanted Black customers' money but wouldn't provide advertising revenue to Black-owned media that served those same customers.

Harlem street scene, May 1943. Photographer Gordon Parks documented Harlem during the height of the 'Whiskey Rebellion' campaigns. The storefronts and businesses visible in this scene were often targets of organized boycotts demanding that companies hire Black workers and support Black-owned media. Photo by Gordon Parks, Library of Congress FSA-OWI Collection, public domain.

The "Don't Buy Where You Can't Work" Campaign

The organizing began in the early 1930s with the "Don't Buy Where You Can't Work" campaign that swept through Black urban communities. Harlem activists, led by ministers, community organizers, and labor activists, identified white-owned businesses that profited from Black customers while refusing to hire Black workers.

Liquor stores became a primary target. The campaign organized boycotts of stores that wouldn't hire Black employees, picketed outside these establishments, and published lists of businesses that discriminated. The message was simple: if you want Black customers' money, you need to provide Black people with jobs.

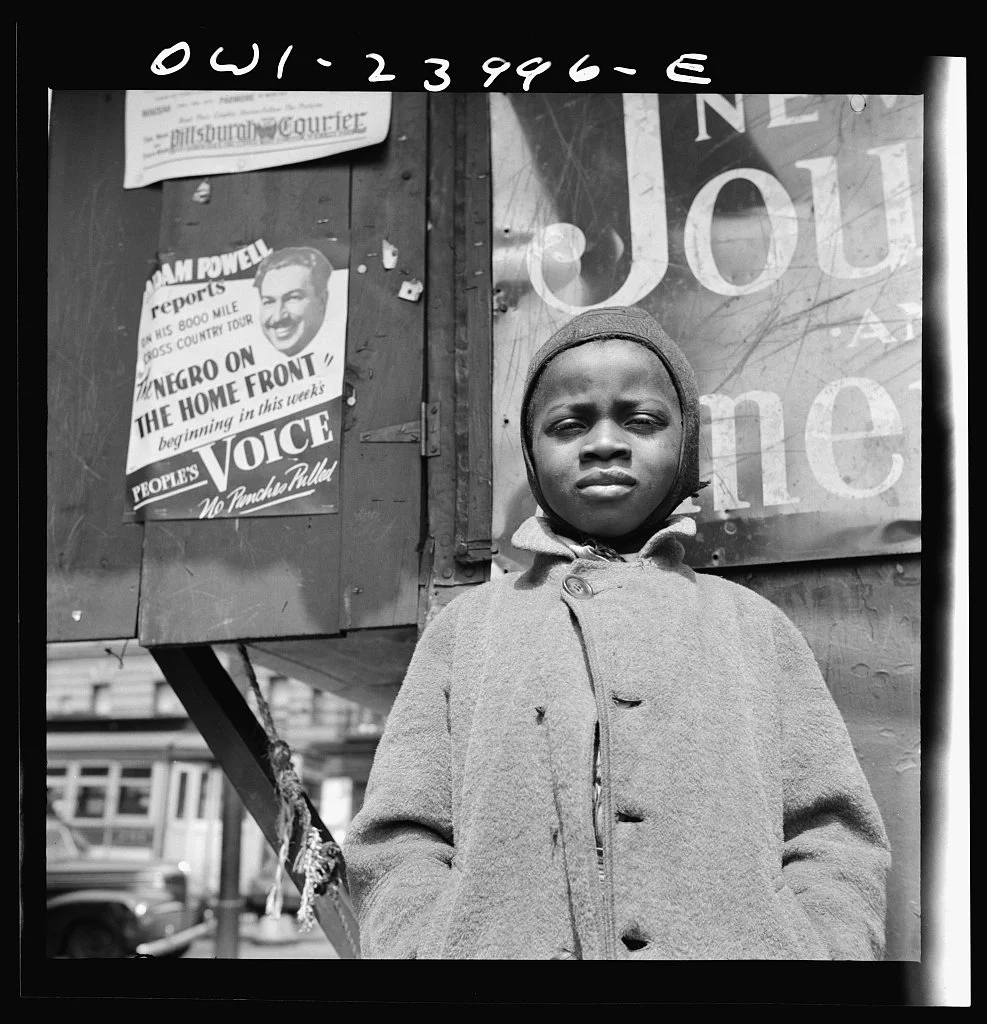

Harlem newsboy, May 1943. Black newspapers like the Amsterdam News and People's Voice were crucial to the Whiskey Rebellion, documenting liquor industry discrimination and organizing boycott campaigns. Yet liquor companies refused to advertise in these publications despite profiting heavily from Black customers. Photo by Gordon Parks, Library of Congress FSA-OWI Collection, public domain.

The campaign achieved early successes. Some stores, facing sustained boycotts and declining revenues, agreed to hire Black clerks and managers. But the liquor industry's response was also swift—many stores simply moved to employ one token Black employee while keeping hiring otherwise segregated, or they fought back through the courts claiming that organized boycotts violated their business rights.

The legal battles that followed established important precedents. Courts generally ruled that peaceful boycotts and picketing were protected activity, giving civil rights activists a legal framework that would be used in later campaigns across the South. But liquor companies also learned to fight more subtly—they made minimal concessions while maintaining discriminatory practices in hiring, promotion, and ownership.

The Distributorship Fight

Beyond retail employment, activists fought for Black access to liquor distribution—a far more lucrative sector of the industry. Distributorships held exclusive rights to sell particular brands to retailers in specific territories. These distributorships generated substantial profits but were entirely controlled by white-owned companies.

Black entrepreneurs who attempted to enter liquor distribution faced systematic barriers. Manufacturers refused to grant distribution rights to Black-owned companies. Banks wouldn't provide financing. Industry associations excluded Black applicants. The result was a complete lockout from an industry sector that generated significant wealth.

Harlem activists organized campaigns demanding that major liquor brands grant distribution rights to Black-owned companies. They targeted specific brands for boycotts, organized protest campaigns, and used their purchasing power as leverage. The campaigns argued that brands profiting heavily from Black consumers had an obligation to provide economic opportunities to Black entrepreneurs.

These campaigns achieved limited success. A few Black-owned distributorships were eventually granted rights to distribute certain brands in predominantly Black neighborhoods—essentially creating a separate and unequal distribution system where Black distributors could only access the less profitable territories that white distributors didn't want.

The Advertising Boycott

One of the most sustained elements of Harlem's Whiskey Rebellion focused on liquor industry advertising practices. Major brands advertised heavily in mainstream publications but refused to place ads in Black newspapers and magazines, even though Black consumers represented a significant portion of their customer base.

The refusal to advertise in Black media wasn't just about marketing strategy—it was about denying revenue to Black-owned businesses. Black newspapers depended on advertising revenue for survival. When liquor companies refused to advertise despite selling extensively to Black customers, they were effectively extracting wealth from Black communities while starving Black-owned media of resources.

Activists organized around this issue throughout the 1940s and 1950s. The Amsterdam News, Harlem's leading Black newspaper, published exposés documenting how liquor brands profited from Black consumers while refusing to support Black media. Community organizations organized boycotts of brands that advertised in white publications but not Black ones.

The campaigns eventually forced some concessions. Major liquor brands began placing limited advertising in Black publications, though often at lower rates and with smaller budgets than they devoted to white media. The pattern established during this fight—Black consumers having to organize and protest to receive basic respect from companies profiting from their business—would repeat across multiple industries.

Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and Political Pressure

Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., pastor of Harlem's Abyssinian Baptist Church and later congressman, became one of the most prominent leaders of Harlem's fight against liquor industry discrimination. Powell understood that the liquor industry's discriminatory practices represented a broader pattern of economic exploitation that civil rights activism needed to address.

Powell organized coordinated campaigns combining boycotts, political pressure, and media attention. He used his pulpit at Abyssinian Baptist Church—one of Harlem's largest and most influential congregations—to mobilize community support for boycotts. He published articles in The People's Voice, a Black newspaper he co-founded, documenting liquor industry discrimination. And later, as a congressman, he introduced legislation targeting discriminatory practices in industries receiving government licenses or contracts.

Powell's involvement brought national attention to issues that had been mostly local campaigns. His ability to mobilize both religious and political constituencies made the liquor industry campaigns more effective and more difficult for companies to ignore. The combination of grassroots organizing and political leadership that Powell embodied would become a model for civil rights activism in the 1950s and 1960s. SOURCE

The Industry Fights Back

The liquor industry didn't simply accede to activist demands—they fought back aggressively through multiple strategies designed to undermine the campaigns while appearing to make concessions.

Token hiring became a primary industry response. Companies would hire one or two Black employees in visible positions while keeping overall hiring segregated. They'd grant one small distributorship to a Black-owned company while keeping lucrative territories reserved for white distributors. They'd place a few small ads in Black newspapers while devoting major budgets to white publications.

These token gestures were designed to split the activist coalition. Some community members would see any progress as success and stop supporting boycotts. But many activists recognized token changes as attempts to appear responsive while maintaining discriminatory systems.

The industry also fought through legal challenges, arguing that boycotts violated businesses' rights and that protesters were interfering with commerce. They sought injunctions to prevent picketing and filed lawsuits against activist leaders. While courts generally protected peaceful protest, the legal costs and threats served to intimidate some activists and drain organizational resources.

Perhaps most insidiously, the industry began selective relationship-building with Black community leaders. They'd invite prominent Black ministers or politicians to industry events, seek their endorsement, or provide small donations to their organizations. These co-optation efforts aimed to fracture unity and create Black voices defending the industry against activist criticism.

The Intersection With Prohibition's Legacy

Harlem's Whiskey Rebellion took place in the context of Prohibition's racist legacy. The alcohol industry that reconstituted after Prohibition's repeal in 1933 was built on the same racist exclusions that had characterized earlier alcohol regulation.

Before Prohibition, some Black Americans had owned saloons or worked in the liquor trade. Prohibition had systematically eliminated these opportunities—particularly in the South, where prohibition enforcement specifically targeted Black-owned establishments. When the industry rebuilt after repeal, it did so in ways that excluded Black participation.

The post-Prohibition regulatory framework reinforced this exclusion. Licensing requirements, capital requirements for distributorships, industry association controls—all operated to maintain white dominance. The system wasn't accidental; it was designed to keep the valuable liquor trade in white hands even when profits came from Black customers.

Harlem activists understood this context. They recognized that fighting liquor industry discrimination meant fighting systems established during and after Prohibition specifically to exclude Black economic participation. The Whiskey Rebellion was partly about rectifying the theft of economic opportunity that Prohibition had accomplished.

The Victory at Schenley

One of the campaign's most significant victories came in the 1940s when activists successfully pressured Schenley Distillers to change discriminatory practices. The Schenley campaign combined boycotts, picketing, political pressure, and media attention to force the company to hire Black employees, grant distribution rights to Black-owned companies, and advertise in Black publications.

The Schenley victory demonstrated that coordinated pressure campaigns could force even major corporations to change. The company had initially dismissed activist demands, confident that Black consumers would continue buying their products regardless. But sustained boycotts hit revenues hard enough that Schenley eventually negotiated.

The settlement included concrete commitments: specific numbers of Black employees to be hired, distribution rights granted to Black-owned companies in certain territories, and advertising budgets allocated to Black media. While these commitments were limited and required continued monitoring to ensure compliance, they represented real progress.

More importantly, the Schenley victory provided a template. Activists learned which tactics worked, how to sustain pressure over time, and how to negotiate concrete enforceable commitments. These lessons would be applied to campaigns against other companies and industries.

The 1950s-1960s: Expanding the Fight

As the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum nationally in the 1950s and 1960s, Harlem's liquor industry campaigns expanded and intensified. New organizations joined the fight, bringing additional resources and attention.

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), founded in 1942, began organizing direct action campaigns against discriminatory liquor stores. CORE pioneered nonviolent protest tactics that would become central to civil rights activism—sit-ins, wade-ins, and economic boycotts. In Harlem, CORE organized picket lines at liquor stores, documented hiring discrimination, and pressured companies through sustained campaigns.

The NAACP's New York chapter joined the fight, using legal strategies alongside grassroots organizing. They filed complaints with state licensing authorities documenting discrimination, threatened legal action against companies violating civil rights laws, and lobbied for stronger anti-discrimination regulations in the liquor industry.

Local 1199, the hospital workers union that was organizing heavily in Harlem, also joined liquor industry campaigns. The union understood that fighting workplace discrimination across industries strengthened labor organizing generally. They brought organizing expertise, financial resources, and the ability to mobilize large numbers of protesters.

Why This History Was Forgotten

Despite lasting three decades and achieving concrete victories, Harlem's Whiskey Rebellion has been largely erased from civil rights history. Several factors explain this erasure.

First, the campaigns focused on economic issues rather than the more dramatic confrontations over segregation that dominate civil rights narratives. Fights over hiring and distributorships don't produce the same iconic imagery as lunch counter sit-ins or Freedom Rides, making them less memorable and less likely to be featured in documentaries or textbooks.

Second, some civil rights leaders were uncomfortable with campaigns focused on liquor—an industry that raised moral concerns for many religious leaders and that some viewed as harmful to Black communities. This ambivalence meant less promotion of the campaigns' achievements and less effort to preserve their history.

Third, the liquor industry had financial incentives to minimize and erase this history. Acknowledging decades of systematic discrimination would damage brands and potentially expose companies to liability. Better to simply never discuss it and let the history fade.

Finally, the campaigns' gradualism—achieving incremental victories over many years rather than dramatic breakthroughs—makes the story less compelling as narrative. The reality of sustained organizing, repeated setbacks, limited victories requiring continued monitoring, and ongoing struggle doesn't package neatly into inspiring civil rights mythology.

The Tactics That Shaped Civil Rights

Despite its erasure, Harlem's Whiskey Rebellion pioneered tactics that became central to civil rights activism:

Economic boycotts: The sustained consumer boycotts of discriminatory liquor companies established the template for later boycotts—Montgomery bus boycott, Birmingham campaigns, grape boycotts. Harlem activists proved that organized economic pressure could force corporate change.

Direct action: The picketing, protests, and confrontational tactics used against liquor stores prefigured the sit-ins and demonstrations of the 1960s. Harlem activists learned how to organize mass actions, maintain nonviolent discipline, and sustain campaigns over time.

Political-grassroots coordination: The combination of grassroots organizing with political pressure from figures like Powell showed how to leverage multiple forms of power simultaneously. This model would be replicated in Albany, Birmingham, and Selma.

Media strategy: The campaigns' use of Black newspapers to document discrimination, mobilize support, and pressure companies established patterns of media engagement that civil rights organizations would use nationally.

Coalition building: The involvement of churches, unions, political organizations, and community groups in liquor industry campaigns demonstrated the power of broad coalitions—a lesson that would be central to later civil rights successes.

The Incomplete Victory

By the late 1960s, overt discrimination in liquor industry hiring had decreased significantly in Harlem. Black employees worked in liquor stores, some Black-owned distributorships operated, and major brands advertised in Black media. But these victories were incomplete and fragile.

Black employees rarely advanced to management or ownership. Black-owned distributorships remained concentrated in less profitable territories. Advertising in Black media remained a smaller percentage of liquor companies' budgets than Black consumers represented of their customer base.

The fundamental structure—an industry profiting enormously from Black consumers while Black Americans held minimal ownership stakes or decision-making power—persisted. The campaigns had forced modifications to blatant discrimination but hadn't fundamentally transformed industry ownership or control.

This pattern of incomplete victory would characterize much civil rights activism—achieving legal changes and reducing overt discrimination while structural inequalities remained. The Whiskey Rebellion's trajectory presaged broader civil rights movement outcomes: real but limited progress requiring ongoing struggle to maintain and extend.

The Modern Relevance

The issues Harlem's Whiskey Rebellion addressed remain relevant today. The liquor industry still shows patterns of racial inequality in ownership, executive leadership, and marketing practices. Black Americans represent significant consumers of alcohol products but hold minimal ownership stakes in major brands or distributorships.

Moreover, the industry still targets aggressive marketing toward Black communities while facing criticism for contributing to alcohol-related health disparities. The tension between profiting from Black consumers while potentially harming Black communities echoes the exploitation that activists fought in the 1930s-1960s.

The organizing tactics pioneered in Harlem's campaigns also remain relevant. Contemporary movements for economic justice—campaigns for living wages, fights against discriminatory lending, demands for diverse corporate leadership—use similar strategies of consumer boycotts, direct action, and economic pressure.

Remembering the Rebellion

Harlem's Whiskey Rebellion deserves recognition as a significant chapter in civil rights history. For three decades, activists fought a sustained campaign for economic justice against a powerful industry. They pioneered tactics that would shape civil rights activism nationally. They achieved concrete victories that opened employment opportunities and demonstrated that organized economic pressure could force corporate change.

The campaigns weren't perfect. They faced internal disagreements about strategy and tactics. They achieved incomplete victories that required ongoing struggle to maintain. They sometimes accepted compromises that didn't fully address systemic inequality. But they represented real organizing, real resistance, and real achievement by Black activists fighting exploitation.

When we talk about civil rights history, we should talk about Harlem's Whiskey Rebellion. When we discuss economic justice movements, we should recognize these campaigns' pioneering role. When we celebrate civil rights victories, we should include the activists who spent decades fighting liquor industry discrimination.

The story matters because it complicates civil rights narratives in useful ways. It shows economic justice campaigns operating alongside and before the more famous fights against segregation. It demonstrates the importance of sustained organizing over many years, not just dramatic moments. It reveals the challenges of achieving systemic change even after winning specific victories.

Most importantly, remembering Harlem's Whiskey Rebellion honors the activists who fought it—the ministers organizing from their pulpits, the community members maintaining boycotts over months and years, the protesters picketing in all weather, the organizers coordinating campaigns, the journalists documenting discrimination. Their struggle shaped civil rights activism even though their names have been forgotten.

When we drink whiskey today, we should remember that Black consumers' money helped build the industry while Black Americans were systematically excluded from employment and ownership. We should remember the activists who fought that exploitation. And we should recognize that the fight for economic justice in the alcohol industry—like so many struggles for equality—isn't finished but continues in different forms.